The road to Emacs maximalism

Building an Emacs Utopia with hot glue, duct tape and Nix

I’ve stumbled across a method of composing programs that excites me very much. In fact, my enthusiasm is so great that I must warn the reader to discount much of what I shall say as the ravings of a fanatic who thinks he has just seen a great light. (Knuth 1984, 1)

Introduction

A couple years ago I've started watching David Wilson's channel (also know as

SystemCrafters), originally his channel focused heavilly on F# (and that's how I

found him), but eventually he started posting more and "GNU slash Emacs"

content. I lost interest on the channel at the time, while he did indeed

showcase a level of productivity that was way above what I had, I felt like it

could be easily emulated with a combination of Neovim and some other Linux

tools.

Everything changed once I saw his presentation about org-roam, my brain got

hijacked by the idea of testing Emacs. I had previously heard about orgmode

before, but it was never on my radar since it felt like some "Emacs weirdo"

cool-aid. What got me impressed was that I always needed some tool to help me

organize my notes (specially during college where most of my annotations got

lost). To fill this gap, such a tool would need to have the following

properties:

- Document everything that I've done.

- Register and link everything that I've read, preferably by integrating:

- Text

- Math

- Code

- Citations

- Manage and track figures, while maintaing referential integrity.

- Be free (as in freedom) or open source.

Obsidian tickles most of these (if you consider its plugins), but the license is

a little bit worrying and you can bet they will pull an insomnia in the

future. Logseq is a much better alternative in this regard, plus you have the

option of using something much better than markdown or reStructuredText, and that

is org.

(…) trivial usage of Org-mode is nothing more than text editing, from which point the user can start to add special plain text Org-mode elements to the document. Org-mode is therefore easy to adopt and aims to be a general solution for authoring projects with mixed computational and natural languages. It supports multiple programming languages, export targets, and work flows. (Schulte et al. 2012, 2)

Org is a major mode in Emacs, it is also a powerful markup language and I would

argue a better tool than any of the current alternatives. If properly

configured, orgmode can combine writing, planning, scheduling, linking and

programming into a cohesive workflow.

Org-mode extends Emacs with a simple and powerful markup language that turns it into a language for creating, parsing, and interacting with hierarchically-organized text documents. Its rich feature set includes text structuring, project management, and a publishing system that can export to a variety of formats. Source code and data are located in active blocks, distinct from text sections, where "active" here means that code and data blocks can be evaluated to return their contents or their computational results. The results of code block evaluation can be written to a named data block in the document, where it can be referred to by other code blocks, any one of which can be written in a different computing language. In this way, an Org-mode buffer becomes a place where different computer languages communicate with one another. Like Emacs, Org-mode is extensible: support for new languages can be added by the user in a modular fashion through the definition of a small number of Emacs Lisp functions. (Schulte et al. 2012, 7)

Literate Programming

I believe that the time is ripe for significantly better documentation of programs, and that we can best achieve this by considering programs to be works of literature. Hence, my title: "Literate Programming." (Knuth 1984, 1)

I must admit that, even though the idea itself seems interesting, time has proven that "literate programming" the way Knuth is suggesting is impractical, but lets forgive him, it was 1984. When it comes to documentation, I would rather deal with a good type system (like the ones inpired by the ML-family of languages) and/or have proper documentation tooling (hexdocs is the gold standard as far as I could experience).

I'm emphasizing this because org-babel (which is part of org-mode) is a

practical tool to make Emacs a literate programming environment.

Borrowing terms from the literate programming literature,

Org-modesupports both weaving - the exportation of a mixed code/prose document to a format suitable for reading by a human - and tangling - the exportation of a mixed code/prose document to a pure code file suitable for execution by a computer. (Schulte et al. 2012, 12)

Orgmode

Arbitrary Code Execution and Generation

Here's what my blog.org file looks like:

Here you'll find my latest content, projects, tutorials and ramblings. #+header: :exports results #+header: :results html #+NAME: export-posts #+BEGIN_SRC shell dotnet fsi posts.fsx #+END_SRC

it's a single text line that also calls a shell command, dotnet fsi posts.fsx,

posts.fsx is an F# file that generates html content as a huge string:

$ dotnet fsi posts.fsx

<div class="stub">

<h2>

<a href="./blog/20241231-the_road_to_emacs_maximalism.html"> The road to Emacs maximalism </a>

</h2>

<small>2024-12-31</small>

</div>

<div class="stub">

<h2>

<a href="./blog/20240916-you_have_10_seconds_to_nixify_your_dotnet_project.html"> You have 10 seconds to nixify your dotnet project </a>

</h2>

<small>2024-09-16</small>

</div>

# And so on...

This could have been done in any language really, but I felt more comfortable

quickly pulling this in F#, the #+header: :results html makes sure this will be

correctly exported to html once we run the publish.el file (either locally on in

CI).

Roam

Similar to the previous section, my notes are also generated via some hacky F#

script:

This is the place where I dump my Org ROAM notes. #+INCLUDE: ./static/html/graph.html export html #+header: :exports results #+header: :results html #+NAME: export-posts #+BEGIN_SRC shell dotnet fsi notes.fsx #+END_SRC

The difference being that there is an extra #+INCLUDE: directive importing

actual html code. That's where the d3.js graph setup is.

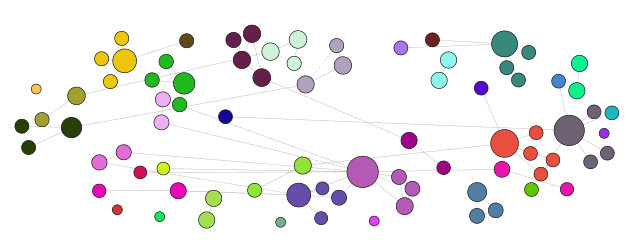

Stealing the Graph

I've blatantly copied from Hugo Cisnero's awesome blogpost a couple years ago

and I really like how he generated a graph out of the sqlite db already used by

org-roam. Some minimal changes were required to render my graph, it is sparser

than his, so forcing a minimum number of communites doesn't look that good (a

quick hack is taking the number of weakly connected components). To build the

graph one just needs to run:

just graph # or graph # inside the Nix shell

Note that this used to be an feature request on Github, until someone created a publish-org-roam-ui github action. Maybe that's what most people need, but it won't work for me, at least in this current iteration of the blog.

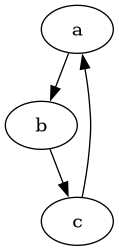

Diagrams as Code

For my current needs graphviz is enough, but I can keep adding similar

tools later:

digraph {

a -> b;

b -> c;

c -> a;

}

The Infrastructure

Knuth has a point about some of the portability issues on his "Literate

Programming" paper, even though the markup language (WEB) was portable to

different systems, the same could not be said of the PASCAL compilers that were

generating the code:

Furthermore, many of the world's PASCAL compilers are incredibly bizarre. Therefore it is quite naive to believe that a single program TANGLE.PAS could actually work on very many different machines, or even that one single source file TANGLE.WEB could be adequate; some system-dependent changes are inevitable. (Knuth 1984, 10)

Technically, any modern literate programming environment (heck any programming

environment in general) is going to suffer from similar issues (instead of

multiple compilers we have multiple package managers and DLL hell). If you use a

python notebook and never bothered to pin your dependencies, or worse, if no one

knows which version of the interpreter was used initially, then give it a couple

months and there's a pretty good chance it will never run.

Nix

To make this less likelly to happen, my development environment heavilly relies

on Nix and devenv. Everything is set in a single flake.nix file, a LaTeX

environment with a couple dependencis, some .NET and Python libs, sqlite, just

and even a custom Emacs to be used in CI, this might seem cursed but it's really

easy to pull this off on Nix:

# (...)

customEmacs = (pkgs.emacsPackagesFor pkgs.emacs-nox).emacsWithPackages (

epkgs:

with epkgs.melpaPackages;

[

citeproc

htmlize

ox-rss

]

++ (with epkgs.elpaPackages; [

org

org-roam

org-roam-ui

])

);

# (...)

this is only used the CI shell, where we require Emacs with a minimum set of

plugins to publish the website, the default (impure) development shell is still

going to pull your local Emacs:

{

# `nix develop .#ci`

# Reduce the number of packages to the bare minimum needed for CI,

# by removing LaTeX and not using my own Emacs configuration, but

# a custom package with just enough tools for org-publish.

ci = pkgs.mkShell {

ENVIRONMENT = "prod";

OUT_URL = "https://schonfinkel.github.io/";

DOTNET_ROOT = "${dotnet}";

DOTNET_CLI_TELEMETRY_OPTOUT = "1";

LANG = "en_US.UTF-8";

buildInputs = [ dotnet customEmacs ] ++ tooling;

};

# `nix develop --impure`

# This is the development shell, meant to be used as an impure

# shell, so no custom Emacs here, just use your global package

# switch back to the CI shell for builds.

default = devenv.lib.mkShell {

inherit inputs pkgs;

modules = [

(

{ pkgs, lib, ... }:

{

packages = [ dotnet texenv ] ++ tooling;

env = {

ENVIRONMENT = "dev";

DOTNET_ROOT = "${dotnet}";

DOTNET_CLI_TELEMETRY_OPTOUT = "1";

LANG = "en_US.UTF-8";

};

scripts = {

build.exec = "just build";

graph.exec = "just graph";

clean.exec = "just clean";

};

enterShell = ''

echo "Starting environment..."

'';

}

)

];

};

the full setup can be found in the main repo.

Continous Integration

Again, I benefit from a somewhat easy to setup CI pipeline thanks to install-nix, it's a copy of what I already do locally. And you can also benefit from faster builds with the magic-nix-cache.

- name: Install Nix

uses: cachix/install-nix-action@v27

- name: Install Nix Cache

uses: DeterminateSystems/magic-nix-cache-action@main

- name: Build website

run: |

mkdir -p "$HOME/.emacs.d/"

touch "$HOME/.emacs.d/.org-id-locations"

nix develop .#ci -c just build

- name: Deploy

uses: peaceiris/actions-gh-pages@v4

with:

github_token: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}

publish_dir: ./public

What is Still Missing

- Anki-Like Flashcards: With either org-drill or org-fc.

- Integration with org-ref:

org-refoffers a suite of tools that would make keeping track of references easier as the number of notes and posts increases. - Remove some of the Polyglot Templating: Although the polyglot usage of

different programming languages here was a good way to show some of orgmode's

source block features, I know my usage of

F#is unecessary, I could have done the same in pureelisp, but I still suck at it. - Not related to the blog itself, but org-agenda looks slick.

Notable Mentions

Hugo

This blog was originally fully integrated with hugo and ox-hugo (first stolen

from my close friend), but eventually I've started facing issues since the way I

organize files (one per post) is not recommended by ox-hugo. The "per-post"

setup actually worked, but hugo is also a project that moves very fast and I

quickly faced a situation where upgrading it broke my workflow, luckily I

develop in a sandbox environment and was able to ignore this versioning issue

for a couple months.

Emanote

Before doing the full refactor and moving it back to a pure org-publish

workflow, I found out about emanote. It is similar to Quartz, but it feels

overall better since the license is AGPL v3. It's also built atop of Markdown,

but there are steps on how to configure this to use org as well. May be a good

choice for people already familiar with Haskell and Nix.

Conclusion

While I haven't moved all my development workflow to Emacs (it might be a matter

of time), Emacs already stole all my note-taking and blogging capabilities and

I'll probably stick with it for a long time. I still hope Neovim gets something

similar, it is already a huge improvement above vanilla vim offered thanks to

many new features (and allowing a real language for configuration instead of

VimL). There is also some work being done in replicating org using lua, but it

would be interesting to see if the community can pull some similar plugins as

well.